Symptoms, Disorders, and Functions and the NIH Domain and the NIH Research Domain Criteria

“The organization of information

actually creates new information.”

— Richard Saul Wurman

Historically, there are two basic approaches to the evaluation and treatment of mental and emotional disorders, and although

they are in some conflict, it is possible to combine them to ensure best practices. These approaches are:

• The disorder-oriented symptom-based approach—epitomized by the DSM-V and its associated practice and insurance policies.

• The function-based approach that focuses on underlying principles — and avoids reference to disorders or stereotyped symptoms in its practice model.

In creating assessments and treatment plans, diverse information can be brought into consideration. This includes:

• Diagnostic interview results

• Structured test results — such as CPT and performance tests

• Tests such as EEG, QEEG, and related physiological data.

There is a need for integration and consensus on how this information can be incorporated in a systematic manner to ensure the best decisions and outcomes. Often, symptoms alone are brought to bear when a prescribing physician may listen to a parent or child, and then select a medication based on that information alone. This may be effective in some fraction of cases, but it ignores the reality that more than one cause can lead to a particular observation — and a basic 15-minute interview is not enough to make that determination.

It takes little reflection to realize that using a symptom-only approach has serious limitations, and may be considered as a defect in the practice model. There are many reasons a particular behavior or complaint may appear, and a symptom-only approach neglects this. Most common disorders such as depression, anxiety, and attention issues are interactive and complex. A child may present with agitation and inattention, when the underlying cause is metabolic — or related to a specific learning disability or a sensory processing disorder.

Another issue with a symptom/disorder-based approach arises when a given disorder might contain many different symptoms, some combination of which comprise the diagnosis. It is possible to have two children with entirely different behaviors and profiles, who share that one diagnosis. From a functional point of view, this does not make sense. To ensure suitable assessment and treatment options, two individuals with different presentations should be differentiated. This is not just an academic point. The different sub-types of ADD, for example, respond differently to medications and other interventions, so that a clear distinction between types is necessary to avoid negative outcomes and abreactions.

Another controversial extreme is to rely heavily on test results and use data as the driving influence. While this may be more physiologically based than behavior and self-report, there is the inevitable trade-off of types of errors that can arise when using data to make a decision. For example:

• Type 1 errors occur when a test result is interpreted too liberally, so that there is a likelihood of a false positive — a misdiagnosis. These lead to stigma, concern, and possibly unnecessary or even harmful treatments.

• Type 2 errors, in which a test result is disregarded for not being extreme enough, resulting in a failure to recognize a bona fide condition in a patient.

Another form of fallacious reasoning results in the tendency to “treat the brainmap.” If the purpose of the intervention is solely to produce a clean map, all that is need is Wite-out, and the map can be cleaned in an instant. Though facetious, this example shows that if you intervene at an inappropriate time in the progression and mechanism of a disorder, you may wipe out external appearance, but can do so without treating the underlying causes.

The integrated model is applied when the practitioner can say “I see these individual functional characteristics, perhaps excesses or deficits, which, within the individual’s environment and demands, are giving rise to the observed thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in this client.” It must be possible to associate the external observations and reports with physiological data that are consistent with — or commonly seen in cases of — these observations. Having gone through this process, it is possible to assign a diagnosis without ambiguity, one that is based on a combination of underlying functional considerations, along with the classical symptom checklists.

Overall, the use of convergent information is essential, and the effort taken to ensure multiple directions of assessment is reflected in a clearer, more informative, and more useful understanding of each client. New technology and clinical science are providing the means to create comprehensive assessments that incorporate behavior, self-report, performance scores, physiological data, and environmental factors. In this way, convergent information allows practitioners to pinpoint their client’s position and trajectory in a multidimensional manner by incorporating multiple levels of consideration.

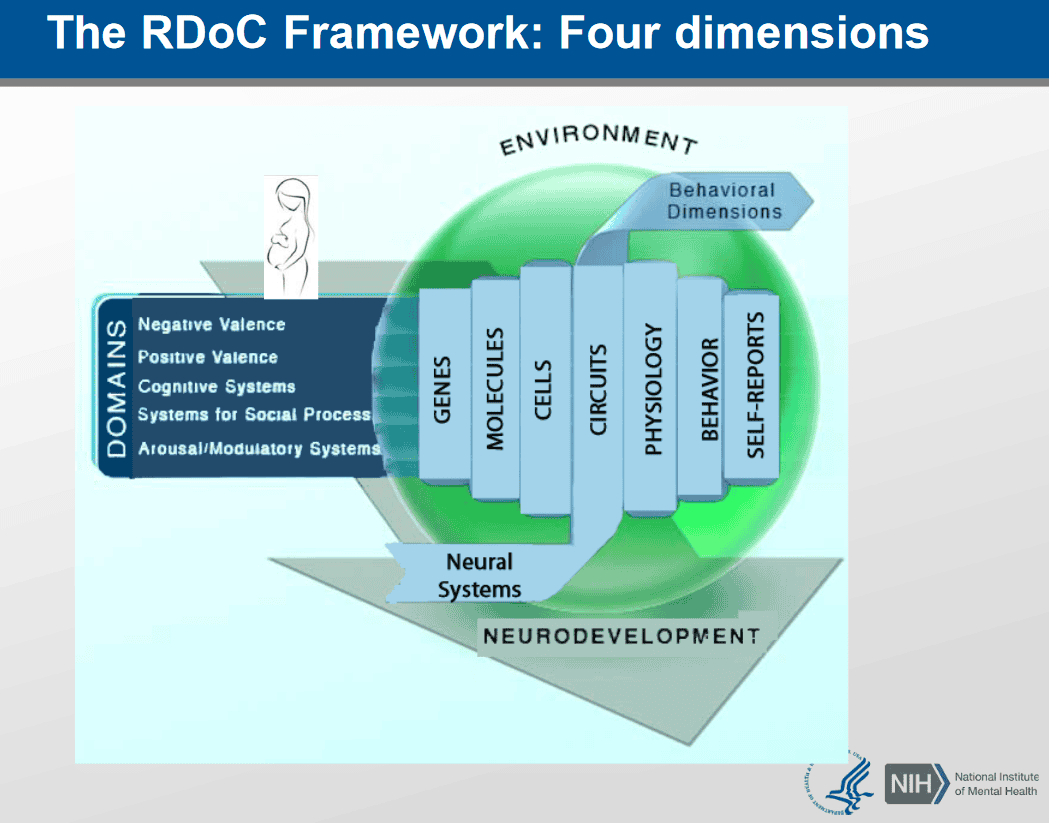

This approach is consistent with the National Institutes of Health Research Domain Criteria RDoC Framework. This model is a four-dimensional space that incorporates the full range of organismic functioning from genetics, chemistry, biology, and behavior in a continuum — with circuits being the binding middle structure.

EEG and QEEG make considerable use of circuit concepts because they measure and quantify neuronal activation and connectivity in a direct manner that is not equaled by any behavioral, metabolic, or structural measure or mapping method. EEG/QEEG provides an ideal rapid, cost-effective, and precise approach to capturing neuronal patterns for assessment, as well as for neurofeedback and related neuromodulation techniques.

Tom Collura

https://iacc.hhs.gov/meetings/iacc-meetings/2016/full-committee-meeting/january12/slides_bruce_cuthbert_011216.pdf

Put it before them

briefly so they will read it,

clearly so they will appreciate it,

picturesquely so they will remember it

and, above all,

accurately so they will be guided by its light.

— Joseph Pulitzer